Introduction

Jeff Bezos left investment banking to sell books online in the late 90’s through a website he called Amazon. Today Amazon has matured into a retail giant, having dethroned Walmart as the most valuable retailer in the US in 20151.

Amazon has not only disrupted the retail world but also sought to take on any industry it relied on in conducting its business. Jeff Bezos has a modern approach to vertically integrating companies. He harnesses the cost-saving benefits while minimising the pitfalls of internal complacency that in the past have eroded the increased margins typically sought through creating these structures. By creating an external customer offering in each of the industries in which it vertically integrates itself, Amazon has converted some of its largest expense line items into revenue generating assets while ensuring it continues to provide superior service levels.

The first example of this strategy was Amazon’s move into cloud computing through the 2006 launch of Amazon Web Services, also known as AWS. Amazon went through a period of dramatic growth at a time when enterprise-class SaaS was not widely available nor economic. Amazon was therefore forced to build its own computing infrastructure. Given the enormous costs associated with this, Amazon decided it would convert the new infrastructure into an external product. Doing so would both offset the internal costs and insure against inefficiency and technological stagnation. AWS is now a US$17.5b revenue business with revenue growth of 42% over the last financial year.

Not long after that came Fulfilled By Amazon (FBA); a service in itself, but in essence a non-core revenue generating entity tasked to reduce one of Amazon’s largest operating costs – fulfillment. This Fulfilment-as-a-Service allows any third-party seller to store their inventory at one (or multiple) Amazon warehouses from which Amazon will pick, pack and deliver each order and even manage the entire returns process, including providing 24/7 customer service. Amazon does not limit this service to orders placed through the Amazon marketplace but extends the offering to all orders placed with the third-party, regardless of the online channel. Customers of Amazon can ship their products directly from supplier to an Amazon warehouse and not directly incur the setup and operational complexity or overheads associated with the warehousing, fulfillment, returns or customer service.

The benefits to Amazon are three-fold:

- Increased utilisation of excess warehousing floorspace

- Reduced last-mile delivery contract rates obtained from its logistics providers by leveraging higher freight volume; and

- Generating revenue from its fulfilment services.

With physical operations currently spanning 14 countries and growing, Amazon employs over 560,000 people and recorded US$178b in revenue during 2017. Jeff Bezos revealed in his annual shareholder letter for 2017 that it had more than 100 million Prime customer accounts2 worldwide, with this number set to grow further as online shopping increases its share versus physical retail spending.

Logistics is a critical operational value driver which enables Amazon to meet and exceed customers delivery expectations. Currently, it is essential for Amazon to partner with a reliable network of logistics providers as well as using their own internal capabilities. This level of service comes at a cost. Amazon’s shipping costs3 grew by 34% to $21.7b in 2017 (2016, 40%; $16b), outpacing ecommerce sales growth of 31% for the year (2016, 25%). This, together with forecasts4indicating that by 2020 the eCommerce marketplace will have 900 million customers spending over a trillion US dollars annually, highlights that shipping will continue to be an area of high cost growth.

To date, Amazon’s business strategy has focused on converting its largest internal operating expenses into revenue generating external service offerings. Could logistics be next? If so, what may it look like?

How has Amazon developed its logistics capabilities?

“We expect our net cost of shipping to continue to increase to the extent our customers accept and use our shipping offers at an increasing rate, our product mix shifts to the electronics and other general merchandise category, we reduce shipping rates, we use more expensive shipping methods, and we offer additional services. We seek to mitigate costs of shipping over time in part through achieving higher sales volumes, optimizing placement of fulfillment centres, negotiating better terms with our suppliers, and achieving better operating efficiencies. We believe that offering low prices to our customers is fundamental to our future success, and one way we offer lower prices is through shipping offers.” – Amazon 2015 financial report

Products sold through Amazon’s global marketplace ship to more than 100 countries5. Despite the high cost to establish capabilities across this global value chain, it has already started investing in this area of its business. It has:

- over 298 fulfilment centres world-wide;

- secured the long-term leasing of 40 cargo carrying aircraft;

- gained approval in 2016 from the Federal Maritime Commission to act as an Ocean Transportation Intermediary (in essence a freight forwarder);

- tested last mile delivery of products not sold via its own eCommerce platform; and

- made substantial technology-based investments over the years to support the fulfilment of its retail business.

In 2016, Amazon bought a stake in two European logistics companies, Yodel and Colis Privé6, gaining access and partial control of a fleet of 6,700 delivery trucks which deliver around 170 million shipments per year in the United Kingdom and France. This has led to Amazon UK delivering around 50% of the goods sold through its marketplace. In September 2015 Amazon piloted Amazon Flex in Seattle, a last-mile delivery service using on-demand contractors. Operations have since grown to include contractors in 50 cities7across the US and have also rolled out to the UK market.

Currently Amazon has over 142 fulfilment centres serviced by over 90,000 full-time employees in the US alone8,9,10. Estimates suggest that including sorting and distribution centres, the number of facilities jump to around 327 in the US10. Globally Amazon is building on this number, expanding its footprint to build a network of facilities which will ensure timely delivery of the products bought through its marketplace regardless of the delivery location. The continual expansion of its network of facilities increases its attractiveness to retailers as a logistics provider. Amazon has fulfilment centres in the US and UK within a 50km radius of at least 80% of thepopulation, allowing it to service most of the population within a relatively short period of time.

With industry leading technology and strong capital investment in its own network of warehousing and distribution centres, including local sortation and data centres, Amazon is well positioned to offer logistics and delivery services to third parties. It seems clear from their pattern of investment in other countries, and their mantra of externalising their largest cost bases to market competition, that an Amazon logistics service in Australia is highly likely. But in what form and when? And will they win over customers of existing logistics companies?

How might Amazon enter the Australia logistics market?

Even though it has the necessary infrastructure in place across the US, a review of both social media feeds and customer complaint sites highlights that it still struggles to meet the demands of customers who are living in remote and rural parts of the US. In Australia, the vast distances required to service the country’s population combined with sparse population density makes establishing a comprehensive logistics operation more difficult. The Australian population is a tenth of that of the US and spread across 7.7 million square kilometres (only 20% smaller than the US), which means the economies of scale for Amazon in Australia are lower than that of its market in the US or UK. The lower population density and large geographical spread will create new challenges for Amazon as to date its success has been achieved in countries which have a relatively high population density across the entire country. Australia has no shared land borders, so Amazon will be unable to leverage off cross-border fulfilment as it does with its European, Mexican and Canadian fulfilment centres.

To be successful in Australia, Amazon would need to improve on the service offering and delivery footprint of Australia Post and StarTrack, which have the most comprehensive B2C parcel delivery services and largest footprint in Australia. Australia Post have access ‘to the footpath’ through their integration of the Letters & Mail and Parcels businesses, providing a low-cost mode for residential parcel delivery. Private global operators such as Toll, DHL, and FedEx also create significant competition for Amazon.

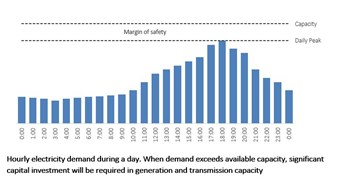

In addition to these challenges, operating costs in Australia are historically some of the highest in the world. High labour costs11, record high property prices12, and rising energy and fuel prices means the outlook for the logistics industry tends to one of consolidation rather than expansion. Wages in Australia are the highest compared to those of developed market peers such as the US, UK, Canada, France, Germany and Japan. Add in a largely unionised workforce with employment guidelines including penalty rates for work performed outside of tradional working hours and it is clear that Amazon will experience signficantly higher operating costs in Australia under a traditional operating model.

Indeed, to enter the Australian market in 2017, Amazon chose to leverage off Australia Post, StarTrack, and Fastway Couriers established networks.

Given these challenges, the path to a logistics service offering for Amazon will likely follow an incremental approach while it builds sales volumes, which is similar to the rollout to date in the US. The current network of facilities in the US enables Amazon to distribute the products sold through its marketplace to 80% of the population in 2 days or less. The network is primarily made up of a complex combination of redistribution centres, fulfilment centres, distribution centres, sortation centres, delivery stations, and Prime hubs.

Redistribution centres are primarily inbound cross-dock (“IXD”) facilities which are located close to major ports, allowing Amazon to streamline the inflow of goods into their network. The fulfilment centres can be broken down further into small sortable, large sortable, large non-sortable, specialist apparel and footwear, speciality small parts, returns processing centres and 3PL outsourced facilities. Amazon Pantry and Amazon Fresh have dedicated ambient, cold storage, and distribution facilities but utilise the existing Amazon network of sortation facilities where possible. Towards the end of 2013 Amazon rolled out the first of its delivery stations. These are smaller facilities compared to its sorting centres and are positioned close to the larger metropolitan cities and neighbouring airports. The main function of these stations is to sort parcels for outbound routes thereby ensuring timely and efficient last-mile delivery in narrowly defined urban areas. The product mix that is sorted and delivered ranges from non-perishable goods to multi-temperature fresh foods (where Amazon Fresh is available). The last-mile delivery from these stations is typically handled by independent contractors, and when available, Amazon Flex drivers.

To gain greater control over its outbound shipping costs and reduce the time required to deliver a product once purchased, Amazon decided to implement larger regional sortation centres in 2014. This has enabled it to shift shipping volume away from FedEx and UPS to the US Postal Service. These sortation facilities are largely stand-alone buildings in which parcels are received from the fulfilment centres and sorted into pallets based on zip code (“post code”) and delivery routes. These pallets are then delivered via road to the respective post office responsible for delivering small packages to the zip code.

More recently, Amazon has reduced its reliance on the US Postal Service for last-mile delivery and has instead utilised independent contractors or its own network of delivery drivers (Amazon Flex). With the introduction of their Prime hubs and delivery stations it will further utilise the sortation centres to deliver to both the hubs and stations ensuring that rapid delivery service levels are maintained. Amazon is also expanding its network of sortation centres to include airport sortation hubs at several smaller airports near major cities in the US13 enabling connectivity between domestic inbound air freight and local fulfilment centres.

During the same year, Amazon decided to rapidly expand its distribution network consisting of smaller buildings situated near to the larger metropolitan areas across the US14. These were given the name of Prime hubs. Amazon curates and stocks the hubs with popular, high velocity items tailored to the customer demographic. These hubs allow Amazon to deliver these select products in less than an hour, effectively becoming the equivalent of a traditional brick and mortar store without having a physical shop front accessible to the customer.

With a fleet of 40 aircraft and 4,000 prime movers distributing products between fulfilment centres, Amazon is building the capability to manage its freight internally. Amazon Flex is a first pass at securing control over the last-mile delivery. It is currently not in the position to meet the demands of fulfilment from the Amazon marketplace but this does allow Amazon to test and gauge any pain points. This would enable them to take the lessons learned from Amazon Flex and its current partnerships with USPS, UPS, and FedEx and implement a last-mile delivery service that would meet both the customer and its own demands.

Last-mile delivery is the final link in the logistics value chain that Amazon will need to establish to operate a comprehensive logistics and transportation network in the US. A hybrid of delivery methods may be used to ensure operational requirements are met on a consistent basis. These range from independent part-time contractors using their own fleet of vehicles (Amazon Flex) to traditional delivery vans and potentially even Amazon Prime drones.

Over the course of 5 years Amazon rolled out a national end-to-end logistics system in the US. Whilst the density and cost challenges of the Australian market will constrain the scope of their offering, Amazon’s activities in other markets strongly indicate it is unlikely to be dissuaded from capturing and internalising important components of the value chain like metro distribution and delivery.

Can Amazon win over Australian customers with a logistics offering?

Why would a business place its reputation in the hands of Amazon, predominately an online retailer, as a logistics partner rather than the established players in the market such as DHL, StarTrack, FedEx, and Toll? Looking at fulfilment from the end-consumer perspective helps provide answers to this question.

A recent report by Temando15, a world-wide multi-carrier shipping platform for commerce, shows how important shipping and last mile delivery is in generating sales and creating a great customer experience. According to the Temando report across the US, UK, and Australia, over 80% of online shoppers find shipping costs are too high. Roughly 60% of all survey respondents said they would turn to a brick and mortar store to purchase an item if shipping costs were too high. In the US, 74% of respondents said they preferred free shipping over fast shipping, while this number grew to 85% when looking at Australian consumers. Most respondents said that they would increase their basket size to qualify for free shipping.

Apart from free shipping, the main driver to convert an online shopping cart to sales was an offering of multiple delivery options. The research undertaken by Temando also indicates that less than 20% of online retailers absorb the cost of regular last mile delivery of a product; that is, over 80% pass this cost on to the end-consumer.

In the US, where online shopping is more established, consumers were found to be looking for new alternatives to standard and express delivery, demanding hyper-local, same-day, specified timeslot, and weekend delivery options. There is still a large gap between consumer demand and retailer offerings, however, with less than 30% of retailers offering these options.

Therefore, retailers require a logistics partner that can offer competitive rates across a broad range of flexible delivery options, whilst also ensuring any requirement for reverse logistics and real-time delivery tracking is taken care of. As online sales grow, retailers will need to ensure their logistics partners are able to scale alongside them to absorb the increased demand for shipping, both locally and internationally.

Retailers can and are pushing their logistics partners to make the necessary investments in operating flexibility and technology innovation to deliver on their customer’s needs, and logistics partners are responding, as evidenced by the increasing spread of features such as real-time tracking. From a pricing perspective, however, negotiating leverage is driven principally by volume; the number of items that a retailer has to ship. Without a large volume of goods, in one-on-one negotiations with a set of logistics partners the individual retailer will usually be stuck paying rack rates.

Intermediaries such as freight brokers and shipping platforms like Temando has stepped into this gap, becoming quasi-freight-forwarders in that they accumulate volumes and stream them to shippers based on the most attractive rate and performance for particular services. Ultimately, though, they are still only on-selling the services of the established logistics providers, which means that they have little control of the value-added features desired by end-consumers.

This indicates that the potential customer profile of an Amazon Logistics Service would be a customer that does not have sufficient volume to negotiate better shipping rates by themselves. Customers would be micro to mid-sized businesses who trade predominately through an e-commerce channel and who don’t have the infrastructure or management resources required to operate a logistics function internally. Across the US, roughly 68% of online retailers shipped 1,000 articles or less per week on average, with almost half of these retailers having average weekly shipping volumes of no more than 100 articles. Retailers of this size are categorised as micro to small retailers and are ideally suited to an Amazon logistics service offering due to their low volume, increased need for reliable and scalable logistics capabilities, and limited ability to invest in their own logistics infrastructure.

Interestingly, this customer profile mirrors closely Amazon’s original AWS target client – small and in need of on-demand scalable infrastructure but without the capital to invest.

Amazon, then, is well positioned to provide a third-party logistics service given its understanding of online retail and the importance of customer satisfaction. It has already enhanced the parcels delivery experience for its customers by providing not only same day delivery but taking it a step further with a hyper-express delivery option, providing expedited delivery from online checkout to delivery in two hours or less. Throughout the fulfilment and delivery process the consumer is notified of key parcel movements, enabling them to better understand the estimated delivery time. With their own service, they can control the entire logistics process and also take market share from existing logistics providers who are unwilling or unable to keep up with the demands of the B2C market.

What does this mean for eCommerce senders and logistics providers?

In its 2016 annual report16, Amazon emphasised the value in rapidly expanding global operations, increasing both its product and service offerings, and scaling the infrastructure to support both its retail and service businesses. Speaking at a symposium in Washington, D.C. on “The Future of Freight” in September 2017, David Bozeman, Vice President of Amazon Transportation Services, highlighted that to meet customer demand, Amazon has had to systematically build out its sortation centres, linehaul middle-mile and air network. He mentioned that due to the sheer volume of freight that is being generated through the online retail channel, Amazon does not believe there is any one entity that has the capacity to handle the entire demand.

At the time of writing this article, eligible third-party sellers can secure space on an Amazon controlled ocean vessel allowing them to ship products world-wide. Sellers can use Amazon Prime’s logistics services which consists of growing truck and trailer and aircraft fleets to distribute products both within the US and abroad. FBA allows third parties to store their inventory across the globe at Amazon’s fulfilment centres, from which Amazon will take care of the end-to-end fulfilment process. Bloomberg has also reported17 late last year that Amazon is in the process of piloting “Seller Flex”, a service which will pick up packages from third-party warehouses and deliver these packages to a customer’s home. If “Seller Flex” was to be rolled out nationally across the US, it would effectively enable Amazon to manage and control its entire logistics supply chain. Once this is achieved, it could have the capacity to offer all or part of these services to third-parties.

From an Australian perspective, Amazon’s infrastructure is embryonic with one fulfilment centre in Melbourne and a second very large fulfilment centre currently being built in Sydney. A simplified FBA offering has only recently become available to third-party sellers which does not yet enable sellers to fulfil orders across external channels. In its current state Amazon in Australia does not appear to have the structures in place to offer an end-to-end logistics solution to third-parties. Without dedicated sortation centres or fleet of vehicles to enable last-mile delivery, an Amazon last-mile delivery service is not possible, and so shippers will need to continue to rely on established providers.

For logistics companies, however, the signs are ominous. Amazon has established the core components of an end-to-end logistic supply chain in its other major markets, and there is no reason to believe that they will leave the Australian market alone despite the challenges presented. Certainly, warehousing, distribution, and last-mile delivery services will be on their radar. We can expect that within 5 years, with internal and third-party volume, they will develop their own express last-mile delivery services in major capitals. In response, Australian logistics companies need to pay closer attention to their service offerings and competitiveness in their long tail of smaller customers. Whilst major shippers have historically driven their volume and consequently held their focus, their overall profitability has typically been low. The competitive changes that Amazon will help accelerate may mean that the incrementally profitable long tail of customers instead chooses to partner with a company who intimately understands the challenges and needs of the B2C market.

About Pacific Consulting Group’s Freight and Logistics practice

PCG’s Freight and Logistics practice has delivered profit and productivity improvement for leading companies around the world. We have worked in partnership with senior leaders across industry segments like parcel express, road/air/rail freight and intermodal providers, last-mile specialists, and 3PL. Our superior analytics, commercial focus, and industry experience have allowed us to deliver outstanding outcomes.

References

- By market capitalisation: “Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace”. The New York Times. August 16, 2015

- https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/ data/1018724/000119312518121161/d456916dex991.htm

- FY16 Annual results show $17.6 billion in fulfillment expenses, of which $16.2 billion of this cost relates to shipping.

- Reseach report compiled by Accenture and AliResearch (Alibaba Group’s research arm).

- https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/ customer/display.html?nodeId=201074230

- http://fortune.com/2016/01/11/amazon-french-delivery/

- https://flex.amazon.com/

- https://www.amazon.com/p/feature/98dnmkwyztuv8ur

- https://www.businessinsider.com.au/amazon-warehouse-locations-in-us-2017-9?r=US&IR=T

- http://www.mwpvl.com/html/amazon_com.html

- https://www.conference-board.org/ilcprogram/index.cfm?id=38269

- http://www.demographia.com/dhi.pdf

- http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=176060&p=RssLanding&cat=news&id=2241026

- https://qz.com/636404/how-amazon-is-secretly-building-its-superfast-delivery-empire/

- Temando – State of Shipping in Commerce Report 2017 (http://temando.com/en/resources/research)

- Amazon Annual Reports (http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=97664&p=irol-reportsannual)

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-05/amazon-is-said-to-test-own-delivery-service-to-rival-fedex-ups